Cats and Pacts and Pspspspsps

Mmmmm free lunch yum yum yum

Topics: Prediction markets, motivation, social costs, and cats

Disclaimer: I am not very well researched in basically anything. If I am wrong in my facts or reasoning, please correct me in the comments, on a train, or in the rain. If you enjoy the piece and think others will too, feel free to share it the world over.

I. Cat Magic

Pspspspsps works on cats. I’ve tried getting the attention of strays with plenty of other phrases. It’s a fun game which is almost always futile. “Cat! Kitty! Kitty kitty kitty! Gato! Gatito? Puh, puh, ssssssss,” useless. The feline target couldn’t care less. Her neck doesn’t turn, her paws don’t pause. Finally, I use the cheat code: “pspspsps!” The cat’s eyes dart to me, ears twitching, absolutely laser focused on my face. Sitting in a park once, I watched a cat weave around the legs of a bench. It settled in the sun for a while, then walked off behind the bench and I lost sight of it. Wondering if it would reappear, I said the magic words, and ta-da! The tiny head popped up from behind the bench, eyeing me like prey.

Lund University in Sweden has done a lot of research into “Cat-human communication,” and find a pretty convincing cause for the phenomenon—cats are much more sensitive to high frequency noises than humans, an evolutionary quirk that makes sense when you consider the rodents they hunt. Hissing–esque syllables like “sw” and “ts” and of course “ps” contain these high frequencies. This type of cat calling can be seen across languages: “ksksks” in Russian, “pisipisipis” in Turkish, and “tstststs” in Hungarian.

In fact, this is built into a common English word for cat, “pussy.” The origin of the word is closely tied pspsps effect. “Pussy” branched from the word “puss,” a very common name for pet cats since at least 1520, and probably even earlier. Many a pet owner has called their pet again and again to no avail. At some point, people realized it works much better if saying your cat’s name makes them think you sound like lunch.

Unfortunately, all of this science obscures the most important mechanism behind the “pspsps” phenomenon, which is of course magic. Perhaps not fantasy magic, but at least a sort of free lunch magic that I am not accustomed to using in the real world. It reminds me of video games like Zelda, where just learning the words to a spell or the notes to a song grants the player a new ability. Saying “pspsps” sparks that same sense of excitement. How often does “one simple trick” actually improve your life, at no cost? At least once, clearly. Let’s search for more.

II. The Cost of Motivation

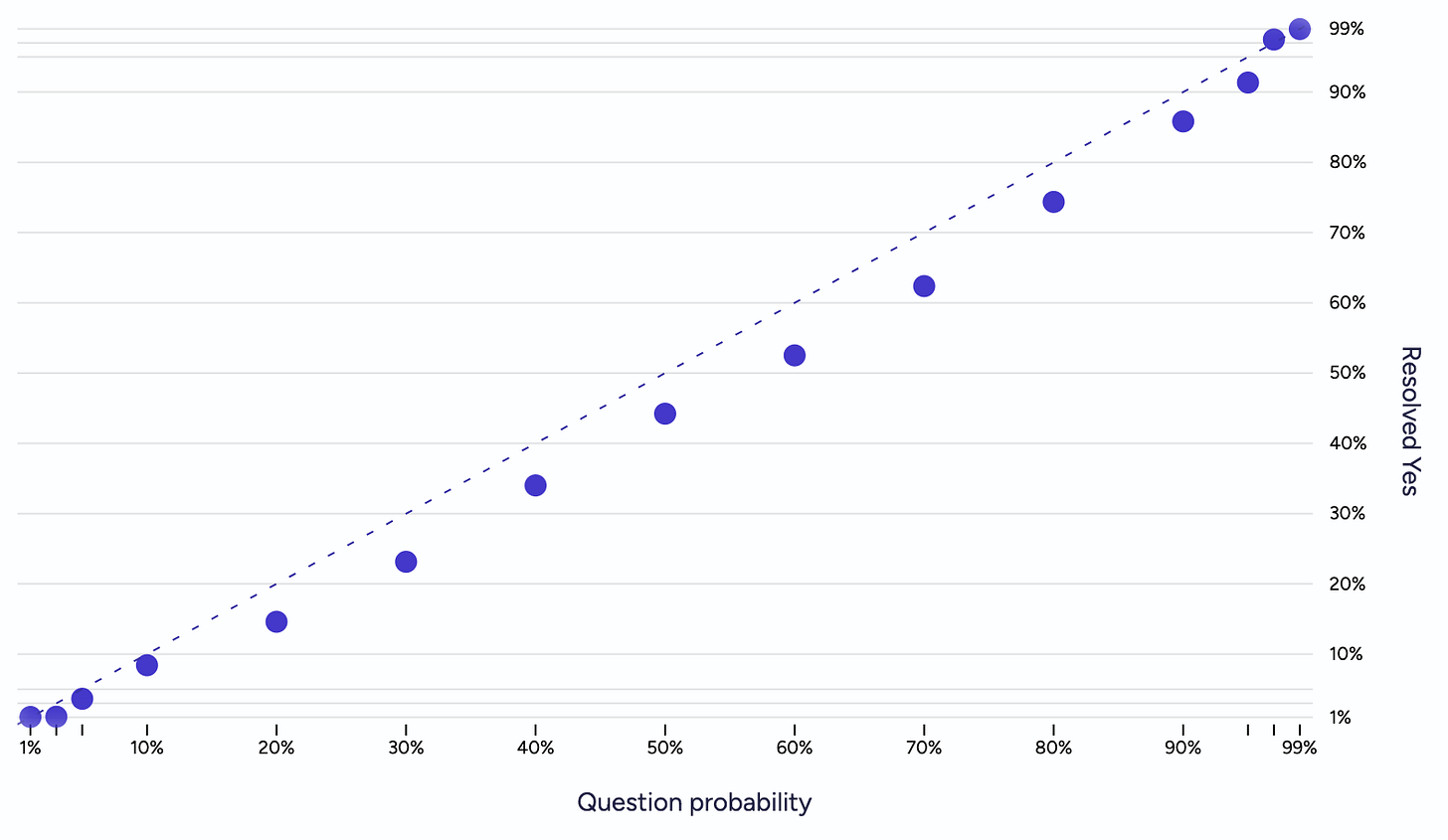

Manifold is a website where users can create and bet on markets about almost anything: who will be president in 2025, when AGI will end the world, or whether they will meet their wife that month. Other users bet their fake money on the outcomes, and the markets adjust to reflect the crowd’s view of the probability of the event. These crowds live up to their vaunted wisdom; in the chart below, we can see that the markets are pretty well calibrated. Manifold users tend to over rate the likelihood of things happening, but only by a few percentage points. If a market says that a given event has an 80% chance, it happens 74% of the time.

This is great! Experts suck at predicting events, and I don’t want to hire a team of super-forecasters to tell me how likely it is that I’ll fall down the stairs this month. Plus, Manifold users bet fake money called “Mana,” which makes it legal in the United States. The markets are zero sum between users in terms of Mana, and they all seem to have fun while they make and lose fake currency betting. Then, their combined play allows Manifold to spit out accurate predictions which would otherwise be hard to come by about a whole array of events. Smells like more free lunch to me.

A few Manifold users have found a totally different way to get something out of the website. They create motivation markets.

While markets aggregate information, they also influence behavior. If there is a 50/50 market open with infinite liquidity on whether Ben Pomeranz will convert to Christianity this year, I could buy two billion yes shares and make a billion dollars by converting to Christianity. I wouldn’t, but I could. This becomes an issue with markets like “Will Mr. Smith die this week?” which is why they are banned. Motivation markets take this side effect and utilize it as a tool.

Here is how you can make your very own motivation market. First, decide upon a clearly definable thing you want yourself to do, like read 3 books in July of 2024. Then, create a market with the following conditions: if you don’t read the books, the market resolves to No. If you do, the market resolves to Yes. Then, you can literally bet on yourself, and the haters might bet against you, and that motivates you to succeed. You can show the haters and keep your money just by reading 3 books. The Brothers Karamazov is already halfway finished.

You, the motivation market maker (mmm!), want there to be lots of people betting against you, to get that real chip on your shoulder. In a regular market though, there isn’t much reason to expect people would bet against you once the probability is sufficiently low. One solution to this is to keep pouring more money into yes, driving up the probability of the market and making it worthwhile for people to bet against you. You promise that you’ll keep your reading motivation market at 95%, betting yes over and over, no matter how many naysayers bet that there is a >5% change that a book will remain unread. If you care about Mana, this should create a lot of incentive to read the books, because otherwise you will lose lots of it.

Another option is to promise that even if you succeed, you won’t take anyone’s money–everyone will just get their money back. That way, you can just bet a set amount of Mana on yes at the beginning, and there is no incentive whatsoever for anybody else to bet Yes. Lots of people will bet against you at no risk to them, so you can endanger exactly as much of your mana as you want to and still have a crowd betting against you. While neither of these setups give good information about whether you’ll read the books1, they make the stakes higher for you, both emotionally and play-financially.

How well does this work in practice? Well, of the 12 resolved motivation markets on Manifold, there were 9 where the maker succeeded in their goal and 3 where they failed. 75% is not bad, but the aspirations haven’t been very high. One guy kept his workout schedule for two consecutive weeks (each week was a successful market), and another kept the plant “Lil Basil” alive through April. In my view, the most impressive market maker was Mich, who managed to keep their total screen time on social media (including Youtube) under one hour a day for a month. I don’t know what it was before they opened the market, but I assume that was a big improvement.

This is a good system. It has public shaming and financial incentive. It is zero sum play-financially, but positive sum in terms of utility since it also gives the market maker the benefit of extra motivation. Why are there only twelve of these things on Manifold, which is the most popular site I know of for users to make their own markets?

One issue is that it is rare for the average person to be invested in play markets at all. To be motivated by Manifold, a person must either care about Mana or their reputation in the Manifold community, and there are only about 1200 weekly users on the site right now. An ideal motivation strategy would be viable for more than .0004% of America. Of course, there are plenty of people who would get into Manifold if they knew it existed, but there are many more who just would not be interested. What’s worse, even if you are into Manifold the public shame effect only really works if your friends use it too. Many accounts are anonymous, and I care a lot less about revealing myself as a failure to strangers on the internet than I do to my friends. Of course, network effects mean that if you are on Manifold, your friends are more likely to be on it too, but in a group of 1200 this can only go so far. Without the social aspect, motivation markets rely entirely on people caring about their play money.

If people could make their markets with real money, they’d definitely be invested (no pun intended), but that is illegal in the US. While I have hope for the lawyers and crypto bros who are working to make this option commonplace, right now it is a fence most people don’t jump.

And even if people had the option, most people don’t like putting their money where their mouth is—it is frightening to know your cold hard cash disappears if you aren’t the person you say you want to be. Beeminder already exists to let people do this. You create a plan, and they take your money only when you stray from it. It is very effective as a motivator, but it isn’t so popular. Beeminder themselves guess that only about 1% of the population are the types to use it. Weird things feel weird, and self imposed financial penalties are too weird for most people to touch. It doesn’t help that an application like Beeminder appears negative sum to the user: when they mess up, their money floats off into oblivion (Beeminder’s pocket).

Buying motivation is a double edged sword: the more you buy, the more likely it is to be free (more incentive = better odds of success = don’t pay a dime), but the more expensive it is if you end up paying. My guess is that most people don’t think about this in terms of the probabilities, and can’t get over the idea of being charged money, real money, for nothing. Of course, motivation isn’t nothing, but in the situation where people are charged they didn’t get their motivation anyhow. The more people have to bet, the worse the cost looks (even though it is a cost they ideally won’t have to pay), and the less likely they are to bet at all. Now the metaphors are getting mixed: there is no free lunch, unless you risk it for the biscuit.

III. Pact Lunch

Let’s try once more to find a free motivation lunch, one that hopefully isn’t too sour for the risk averse. We saw that motivation markets as they stand usually end up without a personal or social element, leaving only a financial incentive. The market maker gives the naysayers money in exchange for the utility of being more motivated; we’ll measure this utility in “Motivs.” Clearly, these Motivs have value, because the market maker is paying for them, but almost everyone struggles mentally and emotionally to convert them to and from USD. The people who are happy to calculate how much their motivation is worth go do it on Beeminder, but most find that hard. It would be great if we could switch out the Dollars or Mana with some kind of currency that people find more natural to exchange for Motivs.

Well, assume people are willing to trade motivation for motivation. What if everybody instead pays each other with Motivs? I made up a meaningless unit of motivation for no good reason and won’t let it go unused. Hell, let everyone trade Motivs with each other, just for fun. Now, the whole situation is perfectly symmetric: every person is simultaneously giving and receiving Motivs to everyone else. There is no notion of the market maker, it is just a big Motiv hub, where everyone is motivating everybody else. This is starting to smell like something we’d call emotional support, or a running club, or a pact.

Surely there is no free lunch, you say! Where is everyone getting these Motivs to give each other, now that they aren’t paying for them? If everyone is giving and receiving in equal measure, our total motivation doesn’t change. That would be perfectly accurate, if not for the fact that people care about their social standing.

Two things that I value are for my friends to respect me and also for them to have good lives [source required]. Everyone already has plenty of Motivs stored somewhere, set aside to pursue the values they really care about. By positioning some distinct task as a bridge I must cross to be Good Friend, I funnel more Motivs towards that goal. So, if task A is my goal, and task B is my friend’s goal, and we both agree, promise, swear that we will do our respective tasks by Friday, we are relying on each other and know we can help each other by doing our task. My Motivs go towards his task, and his towards mine. This means that if I fail he loses Motivs, and I’ve let him down. Suddenly, my task is a bridge on the way to helping my friend and having him respect me, and this is where I get the extra Motivs. I face the same risk that I did when I used Beeminder, except now the punishment is disappointing my friend. I don’t want to pay this social and emotional price, because I value his wellbeing and our friendship, and this creates the motivation I need to do task A.2

This lunch still carries the risk of a potential cost. However, people are much more open to exchanging social and emotional currency for motivation. People make promises all the time, and it works. While people don’t always tell the truth when they make a promise, they certainly do significantly more often. A priori, I would expect that pacts work even better than promises given their symmetry and inherently actionable nature.

After completing a few successful pacts with friends, I began to wonder why this isn’t an extremely common process. Pacts makes people better at doing difficult things. Many of mankind’s great achievements were difficult. Why don’t we see pact–like agreements in the lives of historical greats? Why didn’t Mozart and Haydn agree to make a Sonata a week? Why don’t LeBron and Steph Curry promise each other that they’ll shoot 400 threes a day? Are these giants of their fields wasting free motivs, throwing out their free lunch? Should they be even better than they are?

I think not, and the reason is kind of obvious. If LeBron thought he could improve his game by spending more time every days shooting 3s, he would. The greats don’t make pacts because they don’t have to. Some people fit neatly into the Szasz/Caplan model of preferences: their stated preferences are perfectly reflected in the actions they take, at least when it comes to what they are good at. Bron trains as hard as he can, exactly as much as he wishes of himself, given the amount of time he has. This completely devalues the motiv; he is saturated with motivation, at least with regards to getting better at basketball, and has no need for more. Even us less motivated folk can relate to this in specific domains—it would be pointless to create a pact to eat or sleep. To some impressive people, what they do is like eating.

Unfortunately, I am not one of these greats. At different times in my life I said that I wanted to avoid getting high, wanted to stretch more, wanted to spend less time on social media. I didn’t do these things, and if you asked me why I wouldn’t have been able to tell you. Then I started making pacts, and all these goals started feeling easy. I’d found the words to a new spell, an (almost) free lunch. Pacts work. If you and a friend have something that you are always meaning to do, but never doing, I highly recommend a pact. Set some ground rules and don’t let each other down. Any given one probably won’t rock your world, but they add up. Pacts have noticeably improved my life. I read a little more, my palms can touch the ground, and I found friends in college without turning to the devil’s lettuce.

Speaking of friends, I made some brand new ones this past weekend at Manifest. Four of us actually agreed to a pact of our own; we each had until the end of June to write and and publish a blog post. I said that I wanted to write this one back in April, but I never did. Luckily, I was only a few Motivs short.

In the first situation, you are obviously keeping the odds at exactly 95%. In the second situation, all the people betting against you with no risk will drive the odds down to 0%. Either way, you gain no information whatsoever.

If this feels kind of fuzzy and confusing, it is probably because it is fuzzy and confusing. I probably shouldn’t have modeled this setup with a currency at all, but it was fun and on theme. If some economist wants to model this more rigorously, you’d make my week

pact to provide free lunch for the other pact-er each day...

Ben 👍